Kirby Hall of Civil Rights

One of the important elements in architectural history is patronage, the influence of the individual or group that commissions a work.

The Kirby Hall of Civil Rights (1929-1930) was donated by Fred Morgan Kirby, a highly successful entrepreneur. At age 23, Kirby had committed his entire savings of $500 in partnership with Charles Sumner Woolworth to purchase a variety store in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Over the years the two men developed this modest investment into the enormous F.W. Woolworth Company.

Although the art within the building now points to a broader notion of Civil Rights, Kirby Hall is a physical realization of Fred Kirby’s belief in American Constitutional law and in the capitalist system. It was constructed during the economic prosperity of the late 1920s between the catastrophes of the First World War and the Great Depression. In the words of its dedicatory description, Kirby Hall was intended to be “one of the outstanding college buildings in America,” and it was rumored to be per square foot the most expensive building of its day.

Over the entrance of Kirby Hall is a bust of The Republic, a symbol both of classicism and–appropriately, for Lafayette–of the French Revolution.

In selecting designers, Kirby and Lafayette approached a famous architectural firm, Warren and Wetmore. The New York City firm was known for such prominent buildings as the New York Yacht Club (1898), the Biltmore Hotel (1914), and its most celebrated project, Grand Central Station (1913).

Warren and Wetmore, led by designer Whitney Warren (1864-1943), built in a Beaux-Arts style, as did Carrère and Hastings, Warren and Wetmore’s chief competitor in New York. One tenet of Beaux-Arts architecture was the belief that buildings could serve as didactic tools. This belief perfectly suited the ideas of Fred Morgan Kirby.

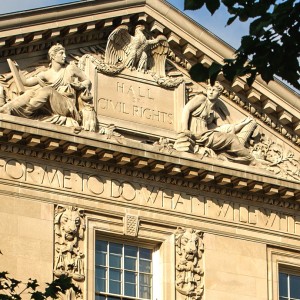

The overall design of Kirby Hall is classically symmetrical in both plan and elevation. The monumental facade is composed of a two-story pedimented gable with a cornice, entablature, and supporting pilasters. It is flanked by wings that step back one level. All of this is in the mode of the architecture of Republican Rome, the Renaissance and English classicism of the 17th century. Kirby would have found all these design sources appropriate, especially the references to England because of his interest in Anglo-Saxon law. Specifically, Kirby Hall is reminiscent of the architecture of Inigo Jones (1573-1652), John Vanbrugh (1664-1726), and Christopher Wren, especially such buildings as Wren’s Pensioner’s Wing, Chelsea Hospital (1683).

One feature largely eschewed by English classicism, but embraced by many other architectural styles, including Beaux-Arts, was elaborate ornamentation. Kirby Hall is notable for its decorative sculpture, which was intended to be instructional. The tradition of relief and free-standing sculpture being attached to architecture to enhance its meaning goes back to the ancient world and was prominent in the elaborate Christian symbols carved on the great medieval churches. In the Renaissance and post-Renaissance, symbols from classical literature were revived to show the roots of Western learning and culture. Unfortunately, this visual language has been all but lost to the modern individual.

Over the entrance of Kirby Hall is a bust of The Republic, identifiable by her Phrygian cap, a symbol both of classicism and–appropriately, for Lafayette–of the French Revolution. In the left side of the pediment is the personification of law, holding the Mosaic tablets and the scales of justice. She wears a laurel crown for glory and reclines next to the scrolls of Roman law. To the right is the figure of Government crowned by oak leaves for strength, grasping the bound Roman fasces for unity, and resting upon the books of Common Law. The symbolism is carried through even in the building’s details: draping the arched west window are the seals of the Thirteen Colonies; under the east windows, Tudor roses, referring to the English origins of our Constitution, alternate with fleurs-de-lis, representing our French connection.

Kirby Hall’s solid grandeur and elaborate, symbolic decor make it distinctive among Lafayette’s buildings.

Kirby Hall’s decorative sculpture was designed and executed by Edward McCartan of New York and approved by the architects and, probably, Fred Kirby. Kirby himself, together with Miller D. Steever, Kirby Professor of Civil Rights, selected the inscriptions carved in bold Roman lettering around the top of the building.

Kirby Hall is one of the rare buildings at Lafayette in that its interior is artistically as important as its exterior. The lobby, including the broad staircase, is spacious and constructed of one of the finest and most expensive materials available, travertine. It contains bronze portrait busts of American heroes from original casts by the important French sculptor Jean Antoine Houdon (1741-1828). The second floor includes the Council Room and the magnificent Kirby Library with its twenty-foot ceiling and oak-paneled book cases. In the Council Room and hallway is displayed a fine collection of portraits of American heroes, given to the college by Allan P. Kirby ’15, one of which is Charles Willson Peale’s (1741-1827) Washington at Yorktown (1779-82).

From “Lafayette College Architecture: In Context” by Robert Saltonstall Mattison. Easton, PA: Friends of Skillman Library, 1991.